Seeing as how I've recently been dealing with a particularly hardy case of writer's block and a few stalled articles, it is probably an appropriate time to delve into one of my trademark in-depth reflections on my somewhat unexciting existence. Yes, it's time for another rambling editorial here on OddBike, at least until I can clear the fog out of my head and start writing meaningful profiles of weird motorcycles again.

As some of my loyal readers will note (those who slogged through my epic USA Tour Travelogue, anyway) I recently announced my intention to bugger off and pack my ass off to Calgary, where I would start my life anew with a post in the motorcycle industry. I did indeed follow through on my threat, and this major moment of transition is what has kept me tied up and limited in my writing capacity in recent months. On reflection it seems a good opportunity to look back on how things have evolved in my life, and how OddBike has grown in the previous year. It was, as really loyal readers will note, the one year anniversary of this site in November 2013, so it seems appropriate to take this belated opportunity to address the development of this here experiment in quote unquote "motorcycle journalism".

At the close of the USA Tour I was filled with an intense wanderlust, a deep longing for a measure of instability in my otherwise dull and routine existence. This was a desire that wasn't satisfied with a few weeks spent on the road, however memorable those weeks may have been. With winter upon me and the Ducati tucked away in the garage, I was desperate to escape, my life turned upside down by the revelation that an entire world was open to me if only I took the opportunity to break away from my dreary and repetitive life. I lived in one of the most vibrant and culturally interesting cities in North America and I felt completely stifled. I was going nowhere, I was doing nothing, my friendships were fairweather and superficial, my career was sliding into miserable repetition, and all around petty politics were conspiring against my personal well-being. I was becoming a shy and withdrawn creature of habit, an inner-city variation on the dull suburbanite existence I despised so much. I felt trapped and I needed to do something about it.

I fielded several wishy-washy job offers from numerous motorcycle related businesses in Calgary. I had no real concrete offers in hand, just a few vague promises and some maddeningly tantalizing “come see us when you are in Alberta” statements. For any sane and rational person it was nothing worth giving up a stable job to pursue, particularly when it involved moving to the other side of the country.

I am not a sane or rational person.

I gave notice at work and started giving away my furniture. I financed a used car and bought a motorcycle trailer. I arranged a sublet in my apartment to take care of the remaining months of my ironclad lease. The announcement that I was giving up my life in Montreal to resettle out West was met with shock from my friends and family, usually followed by a verbal pat on the back for making the effort to move forward with my life. Even my boss of three years was understanding after the initial shock of my resignation passed – he knew well enough that Quebec wasn't the place for me, and that I would have more opportunity to grow in Alberta.

Most people seemed to assume my move was for economic reasons, to pursue the almighty dollar in Canada's oil-rich heartland. Truth is I chose Alberta because it offered the greatest degree of personal freedom, jobs were easy to come by, and my best friend had moved there the previous year. It didn't hurt that it was something new and unknown, far away from anything I had experienced before: I'd never been west of the Great Lakes. What better way to see the rest of the continent than to pack your shit into a car and drive out there? It would be a shift that would herald the beginning of a new attitude and a new stage of my life.

On January 3rd I hitched a trailer carrying my Ducati to a Civic loaded to capacity with my most prized possessions and set out across the country to restart my life 2500 miles away.

This wasn't the first time I'd given up my existing life to reset the clocks. I've often found myself in these moments of renewal, usually following a period of intense soul-searching spurred on by either some trauma or my constant fear of complacency. My time on Earth has been a string of compartmentalized lives, a series of personalities developed and then abandoned in the process of self-improvement. I've struggled with my personal demons and social anxieties since I was a child, and I often found that when all else failed the best recourse was to stop, cut the ties that were holding me back, and start things over. It was often as much about rebuilding my psyche in a new environment, free of pretensions, as it was about escaping my real or imagined failures. Dramatic move aside, Calgary was just the latest reset: a place where there was no reputation preceding me, no skeletons from my past to haunt me. It was an opportunity to remake myself once again, and add another layer to my personality as I shed another life.

I was brimming with confidence and bravado, the uncertainty of my resettlement relieved by the prospect of a clean slate awaiting me in Alberta. I was filled with a happy anxiety, a sense of anticipation for the promise of the unknown. As I eased the car out of my Montreal garage for the last time, I felt alive once again.

I drove across Quebec and Ontario and then crossed into the United States for the majority of the journey, bypassing the treacherous Northern Ontario route in favour of the clean highways and cheap gas south of the border. I passed through Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, Montana, and then crossed into Alberta. Aside from the withering Midwestern cold and some icy roads my journey was uneventful and refreshing, a good chance to ease my mind of the stress of the chaotic transition. The soothing act of being on the road and the uncertainty of tomorrow's destination is something I've always loved but rarely had the opportunity to exercise, given the realities of being a lower middle class retail lackey with more debts than assets. I was anxious to get to Calgary, but I didn't want my journey to end. I wanted to keep driving until I ran out of road.

I recently stumbled onto the latest travelogue by Dennis Matson, aka Antihero. As you might recall I met Dennis in Montreal on the northernmost stop of his more-or-less unplanned 15,000 mile adventure by Ducati Panigale across the USA and Canada. More recently Dennis has been riding along the West Coast of the United States and publishing his usual brilliant musings when he dropped this magnificent bit of insight:

"You can only imagine how the state of mind I'm in contributes to the development of positive, healthy relationships. There seems to be only one constant: that I disappear, and emerge somewhere else, as if my life had folded into two and under the connected planes of the present, moments looped underneath. Moments that only I knew were there.

Travelling is a contradictory, temporary defence against the inevitability of my next trip; an insatiable need that intensifies the more I feed it. I’m still trying to discover just what makes me get up in the middle of the night and leave, what’s making it impossible for me to grow roots (or even want to). I’ve looked at places to buy, places to rent, places to sublet, cities to reside in, but have found none.

So for now I have just one key in my pocket that fits just one motorcycle.”

Then at some point in the travelogue this picture of Peter, a Dutch rider passing through the Pamir mountains in Central Asia, was shared:

|

| Image Source |

I experienced a minor crisis after reading those words and seeing a photo of a man who could only be me in a parallel universe where I lived a far more adventurous life (while maintaining my masochistic penchant for using the most inappropriate Italian machinery for the job). I had kindred spirits across the globe and their actions were beckoning me to join in their maintenance of glorious chaos, where tomorrow remains an unknown and that's the whole point. The weight of my sedentary life slammed into me with all the force that only a twentysomething's existential dread can conjure up. I desperately desired the ability to let go and simply ride wherever the wind took me without any regard for my future. The idea was now firmly planted in my mind and my desire to ride aimlessly was renewed in a most terrible way.

Reality and financial obligations intervened before I was able to have a breakdown and take off for the horizon.

I was now in an unfamiliar city with only the contents of a car to my name. I was fortunate to have a place to crash at my best friend's house in the city, until his girlfriend revealed in no uncertain terms that I was to get the fuck out at the soonest opportunity. Tensions were high and I was forced into panic mode to find an apartment and settle into a job. My fantasies of escaping my obligations were promptly curtailed by the slightly hostile environment I found myself in. I was being pressured to get out, my lack of funds and omnipresent debt threatening to bankrupt me, and I was in a strange city with no income and few contacts.

After canvassing a few potential posts, I accepted an offer to work a parts counter at a large dealership in Calgary. Nothing exceptional or exciting, nothing noteworthy and groundbreaking - certainly nothing that was worth moving across the country for. It is a job. I have the good fortune of working with an excellent group of people and I'm in an environment where I can meet passionate motorcyclists on a daily basis, but the work itself is just another position in just another company for just another middling paycheque – it is a post that offers nothing more in the way of personal fulfilment than any other job I've had. It is an anticlimactic result to my dramatic attempt at renewal but one that was necessary given the circumstances and my fear of spending any amount of time in a state of unemployment.

I recalled some advice JT Nesbitt's had given me prior to my move. He assured me that I had no need to impress anyone by taking a job in the motorcycle industry, noting that I was “already there” with my work on OddBike. He had a point, one that was quickly dawning on me as I settled into yet another safe but unfulfiling stage in my life. JT was referencing his concept of the Bohemian “secret life”, where you accomplish greatness on your own terms, on your own time, outside of your daily grind. He's a man who would be content tending bar as long as he was able to fulfil his true aspirations in his free time - it is a reality he lived for most of his life, his tenure at Confederate and his work with the ADMCi excepted. It isn't cynical or defeatist, it's just a realistic view of the world and an attempt to reconcile one's talent with the reality of existence. The fantasy of the dream career born of passion and sustained by your shining talent is admirable, but barely tenable in the real world. If you hold our passions up and demand to be paid and recognized for your talents, you are corrupting the purity of your accomplishments and risk sliding into the realm of the mundane – a passion can quickly become drudgery if you do it for a paycheque. I can think of few good examples of this, none of which I will share outside of a conversation over a beer lest I alienate some potential future contacts.

Not everyone agrees with this sentiment, and I've been told as much by some who wish a degree of success upon me, but the fact remains I am an ordinary person in an ordinary life and I deserve nothing. I feel that this is the best way for me to operate. OddBike is my creative outlet, my diversion and evidence of my ongoing education – it isn't about making money or catching the attention of some benefactor who will swoop in and save me from my dull existence with a big fat cheque and promise of greatness. I write simply because I enjoy it and because I appreciate weird motorcycles. Somehow that ideal seems incompatible with writing as a career, or at least it would seem that way if you read the drivel being published by “professional” motorcycle journalists who just shovel shit onto the page to meet a deadline.

Maybe I'm wrong. Maybe I could make money with my writing without compromising my ideals or losing my drive. Won't know 'till it happens, I guess. In the meantime this seems an appropriate moment to reflect on how OddBike has developed over the previous year.

I began this site without any real direction or modus operandi. I just found unusual motorcycles fascinating and I wanted to share my interest by writing about the strangest machines I had come across. I began by drawing up a master list of every odd motorcycle I could think of, pouring over the books and magazines I had littering my apartment for inspiration. I began with cursory research and simple articles written using the information that easily fell to hand, but soon my work became more involved and my investigations more in-depth. I developed my own style of telling a story that blended my background in history with my technical knowledge and my passion for bikes. I began contacting designers and owners for more information and ended up conducting impromptu interviews in my own strange way - this usually involved doing the research first, writing the article until I hit a blank spot or vague area, then seeking out the truth from the source. Before publishing I always submit a draft to my interviewees for fact checking, something I doubt most journalists bother doing (I suspect there is some rule against it to maintain objectivity, or some such nonsense).

Soon I noticed that many existing articles were filled with factual errors, contradictions, and outright bullshit - so I stepped up my research to reconcile these details and tell the correct story. What started as a series of rambling little blog posts became an exercise in straightening out the history of these machines.

As time went on, the process became increasingly involved and my subjects increasingly obscure, which has meant a significant slowing of my output. While I used to be able to hammer out an article once a week, I now need at least a month to properly research and edit a full length article. Quality over quantity, or something like that. Keep that in mind if you are breathlessly waiting for me to churn out an endless series of articles.

Throughout my process I have maintained a degree of levity, honesty and opinion to keep things interesting. I write like I think – my thought process is manic, obsessive, and constantly flitting off on tangents. I think this personal touch and erratic writing style is what makes my work unique and appealing, but it is also what puts me at odds with “traditional” journalism. My lack of formal training keeping me within the arbitrarily determined borderlines probably doesn't help. Not that traditional journalism is any more impartial or accurate than what I do – it simply puts on pretences of integrity and objectivity while continuing to fuck everything up.

The response I've gotten from OddBike readers has been completely unexpected and absolutely wonderful. I'm always stunned to get positive feedback from my followers, because I still treat OddBike as my own little fiefdom where I am effectively talking to myself and learning about cool motorcycles along the way. I sometimes forget other people are actually reading this stuff. There is a reason I refer to myself as OddBike's benevolent dictator, stealing a phrase from one of my university political science professors.

In spite of this subjective angle to my work, I've received fantastic words of encouragement and praise from all over the world as well as some really fascinating information and anecdotes about the machines I cover (and some great ideas for future articles). This feedback is what drives me to continue doing what I'm doing. Without it I probably would have let the site wither on the vine many months ago. The knowledge that people care about what I'm doing and are interested in what I have to say has kept me going and continues to inspire me.

I've been stunned by the fact that I have somehow become an authority on the subjects I've covered. I constantly monitor the sources of my site's traffic to see who is reading my work and what they have to say about it. I'm always happy to see that forumites share my articles and these average folks start discussing otherwise completely obscure machines that they hadn't heard about until they stumbled onto my article. Sometimes they show great appreciation for my work and these weird motorcycles, other times they are snide assholes who put down my writing and turn up their noses at these unconventional bikes. In either case I'm pleased that my work has started discussions all over the world and maybe even saved a few topics from complete obscurity. I had no intentions for this to happen, but I'm extremely happy that it has turned out this way – I love weird motorcycles, and I am glad that my work has inspired people to take an interest in these otherwise under-appreciated contraptions.

This position of “authority” on these subjects can also be scary. The first time I discovered I was being cited as a source on Wikipedia inspired a moment of simultaneous joy and terror. The terror comes from the fact that I don't consider myself an expert by any stretch and my work certainly isn't perfect or free of errors. The reality that I'm gradually becoming a trusted source of information is a daunting prospect, but one that drives me to do better work. Hence why I'm putting much more effort into my research and fact checking. I won't be publishing as many articles in 2014, but you can be assured what I do come up with will be far more accurate and more in depth than anything I've published up to now. And when all else fails I'm happy to issue corrections, provided someone out there is willing and capable of pointing out my mistakes. I aim for accuracy and balance in my work, even if it sometimes comes off as opinionated and subjective.

All that to say: a happy belated first anniversary to OddBike, I never expected it to go this far.

Speaking about life as much as about motorcycles, as I grow older and the more I learn, the dumber I feel. I have the sense that as I build my knowledge, I am moving towards the edge of a massive precipice overlooking an endless plain. The plain below is the sum of what I don't know and what I have not experienced. It is beautiful and awe inspiring but threatens to overwhelm me. As I learn more I feel less intelligent because I am increasingly aware of the scope of my ignorance. It is a bit frightening, but if I can control my descent into this landscape I have the possibility of learning more and developing myself as a person and as a writer.

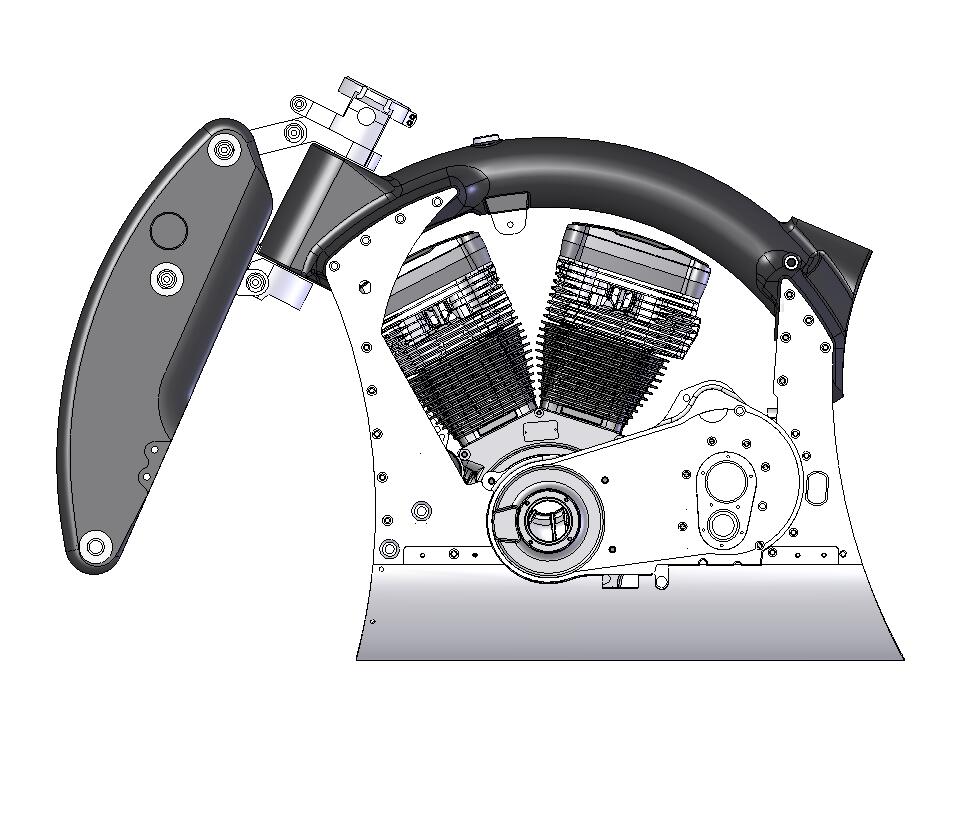

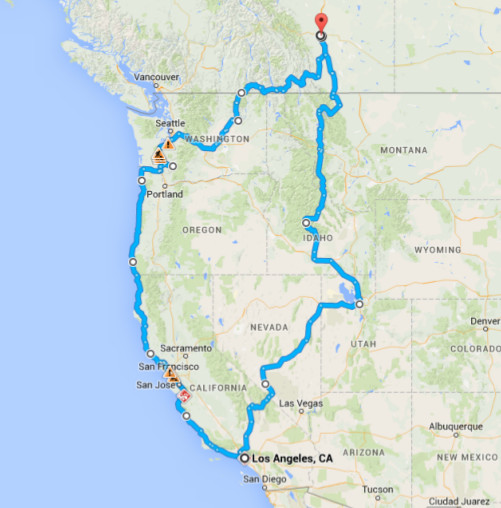

The tempting prospect of travelling and experiencing the world on the back of a motorcycle also inspires an overwhelming sense of inadequacy in the face of what I haven't yet been able to do. Since finishing the USA Tour in October the gravity of the trip has been weighing heavily on my mind and I've been mulling over what will constitute the OddBike USA Tour Part II. Seeing how my first adventure was along the East coast, and I've now moved to the opposite side of the country, it is only natural that I'd head West through the Rockies and then down the Pacific Coast Highway until I hit the Mexican border. After that it is a nice straight route back up north through Nevada and Utah... Where the Bonneville Salt Flats just so happen to be right along my imagined route. So a stop at Speed Week would be in order. Given that I am unable to book enough time off work to accomplish this trip in 2014 (and I already have plans to visit the Barber Vintage Festival this October) I anticipate Part II will happen in fall 2015.

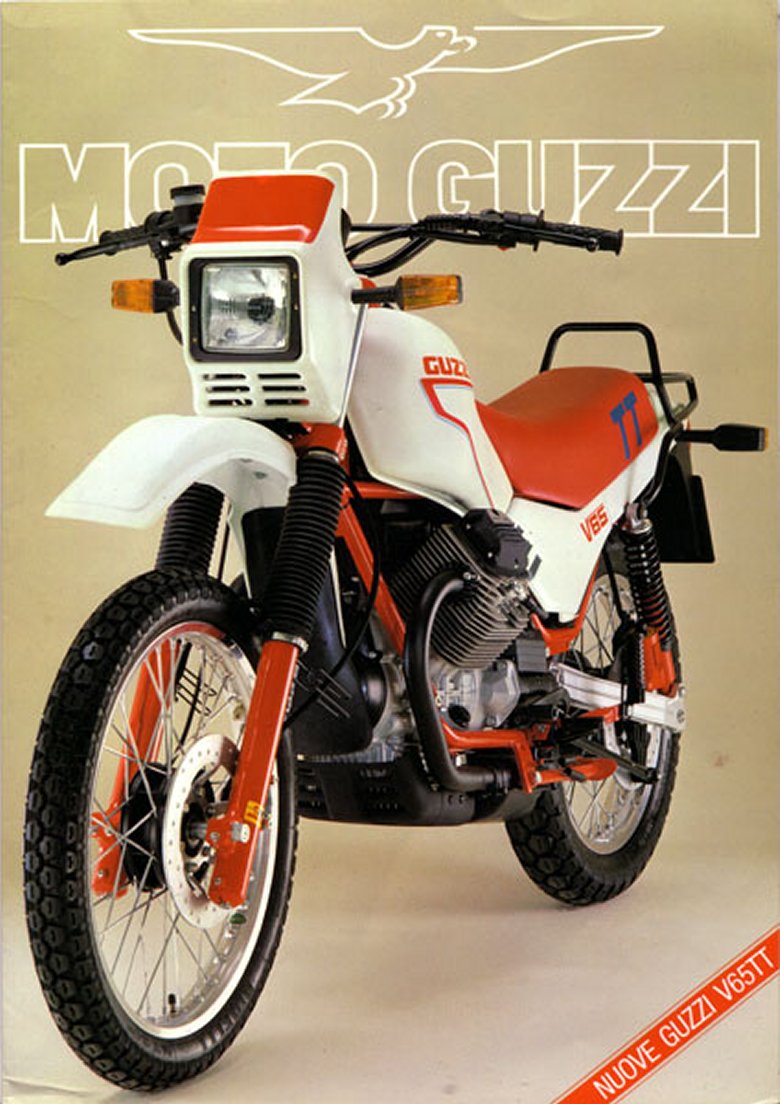

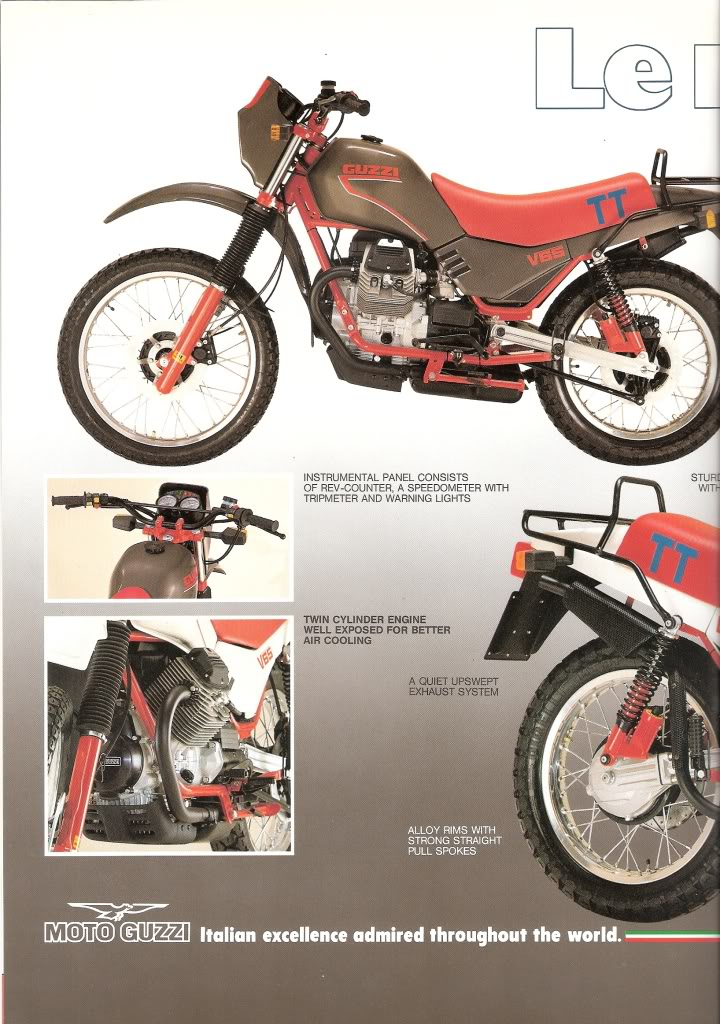

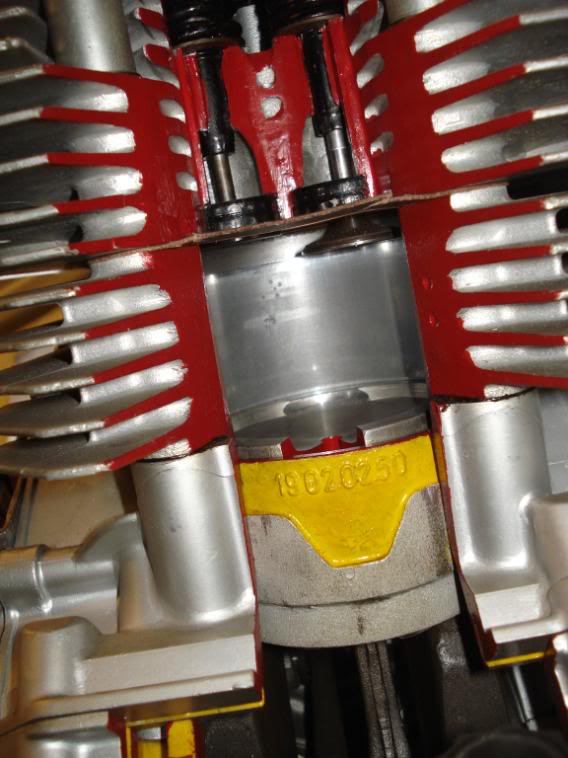

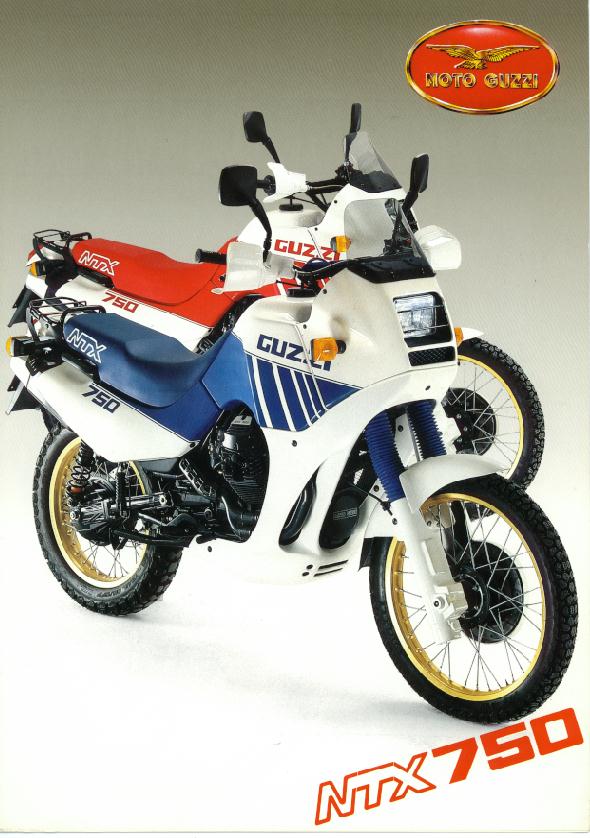

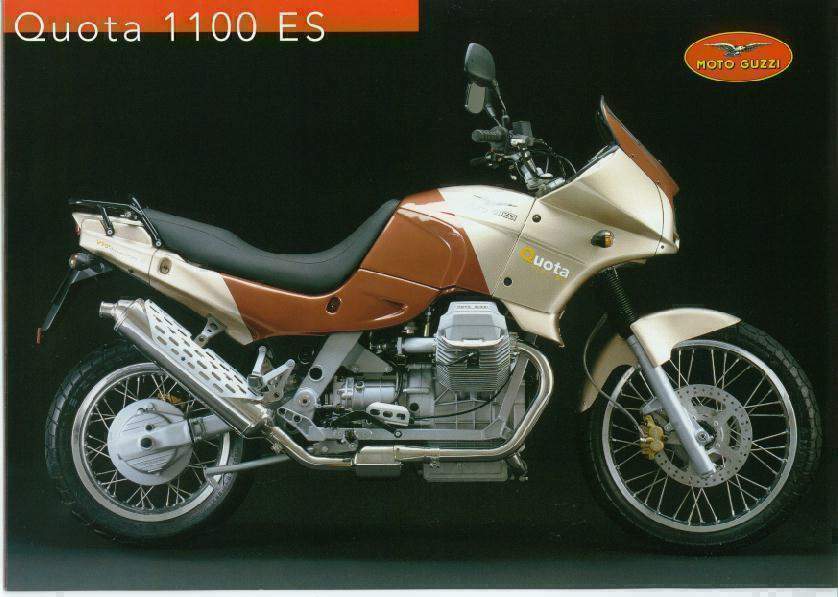

I have been eyeballing the local classifieds, scoping out the prospects of a second bike to use for the ambitious amount of touring duty I anticipate would be necessary to satisfy my insatiable wanderlust. This, of course, is an idle and desperate fantasy given my current financial situation. My desperation at my lack of funds was made worse when a clean, extremely low mileage Moto Guzzi V11 Le Mans was traded in at the shop and promptly dismissed as an Italian piece of junk by the staff, its presence seen as nothing more than a blight on the inventory list. I desperately wanted to rescue it from its unappreciative captors, to release it from its neglect in the backlot. It begged to be ridden. It would be the perfect touring mount for a masochistic Italophile like myself.

Then I recalled that damned photo of Peter the Psychotic Dutchman riding through the Pamir mountains and I was struck by a pang of intense realization – I had to keep using the 916 for touring, and I had to use it for the next OddBike USA Tour. That bike is my signature and it is a part of my personality. If I did Part II on anything more rational it would take away the magic of the journey, and diminish some of the wonderful insanity of the whole endeavour. Showing up at an event 2000 miles from home on a comfy, long legged machine doesn't have quite the same impact as rolling in on a bug-addled, luggage laden, capital-S Superbike that has a reputation for crippling ergonomics, a cantankerous disposition, and nonexistent reliability. That thought of once again inspiring looks of disbelief from candy-assed riders south of the border makes me fiercely desire the arrival of warmer weather so I can blow out the cobwebs and start piling on the miles once again. I've established my own particular brand of insane touring and I should stick to it.

I still want that Guzzi in my garage though. It deserves a good home.