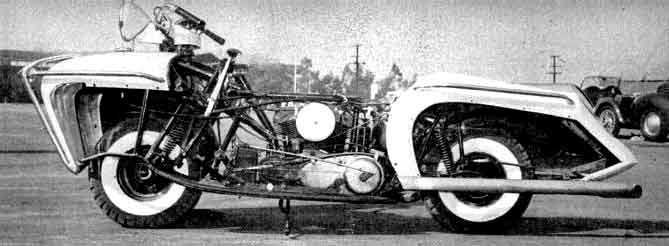

It's the new year, and a time to take stock of the new series of motorcycles that has been trickling out of the gate over the past few months. It’s also the nadir of our Canadian winter here in Calgary, so of course this is the perfect time to attend a flashy, disappointing motorcycle show to examine this year's newly minted cash grabs and dull rehashes in the hopes of finding a few gems in this post-Economic Apocalypse era.

![Ducati Scrambler Ducati Scrambler]()

For some sadistic reason all the major Canadian motorcycle exhibitions are held in the middle of our bitter winter, when we are at least three months away from turning a wheel in anger. It's a chance to admire shiny new contrivances of the two wheeled variety to briefly distract ourselves from the misery of our cold, cycle-free season. Really it seems idiotic. Despite optimistic displays loaded with the latest (and leftover) gear and temporary finance offices throughout the show floor, this isn't the time of year when you are going to be buying bikes. Even taking delivery of them is a chore, shuttling them home on a trailer or pickup just so you can wistfully gaze at them in your garage for 4 months, then take your first wobbly, familiarizing ride on sand and salt caked roads the moment the snow recedes... Test rides are virtually out of the question at Canadian dealerships

any time of the year, outside of heavily regulated demo days where you’ll have to sign up well in advance to ride the latest base model at 5 under the speed limit for 30 minutes.

![KTM Booth KTM Booth]()

Calgary seems to get the short end of the stick when it comes to the show circuit. I've attended the Montreal and Toronto shows in the past, and they are usually well stocked and exceptionally well attended (i.e. crowded as all fuck). This in spite of the significant anti-biker sentiments and associated legislation (not to mention obscene insurance/registration fees) in Quebec and Ontario. Alberta is one of the most free and accommodating provinces in the Confederation and exhibits precious little meddling with its motorcycling population. From my perspective in the industry, motorcycle sales here are fantastic given the population size, with a perpetually booming oil economy feeding an amazing level of disposable income in the general population – rig pigs like their toys. Not only that, but we are less than an hour away from the Rockies and a lot of beautiful motorcycling routes, and not that far away from British Colombia where you can find some of the best roads in North America. Unlike out East, sales of shitty cruisers don’t dominate the market and colour the entire industry with a faux-badass chrome and leather sheen. Here capital-A Adventure bikes are king, along with pure off road machines and a good smattering of tourers, standards and sport bikes. Metric cruisers are sales floor deadweight. People out here appreciate bikes that are versatile and can go around corners, though there are plenty of dorky hipster gangs with unrideable choppers and café-poseurs to keep things balanced.

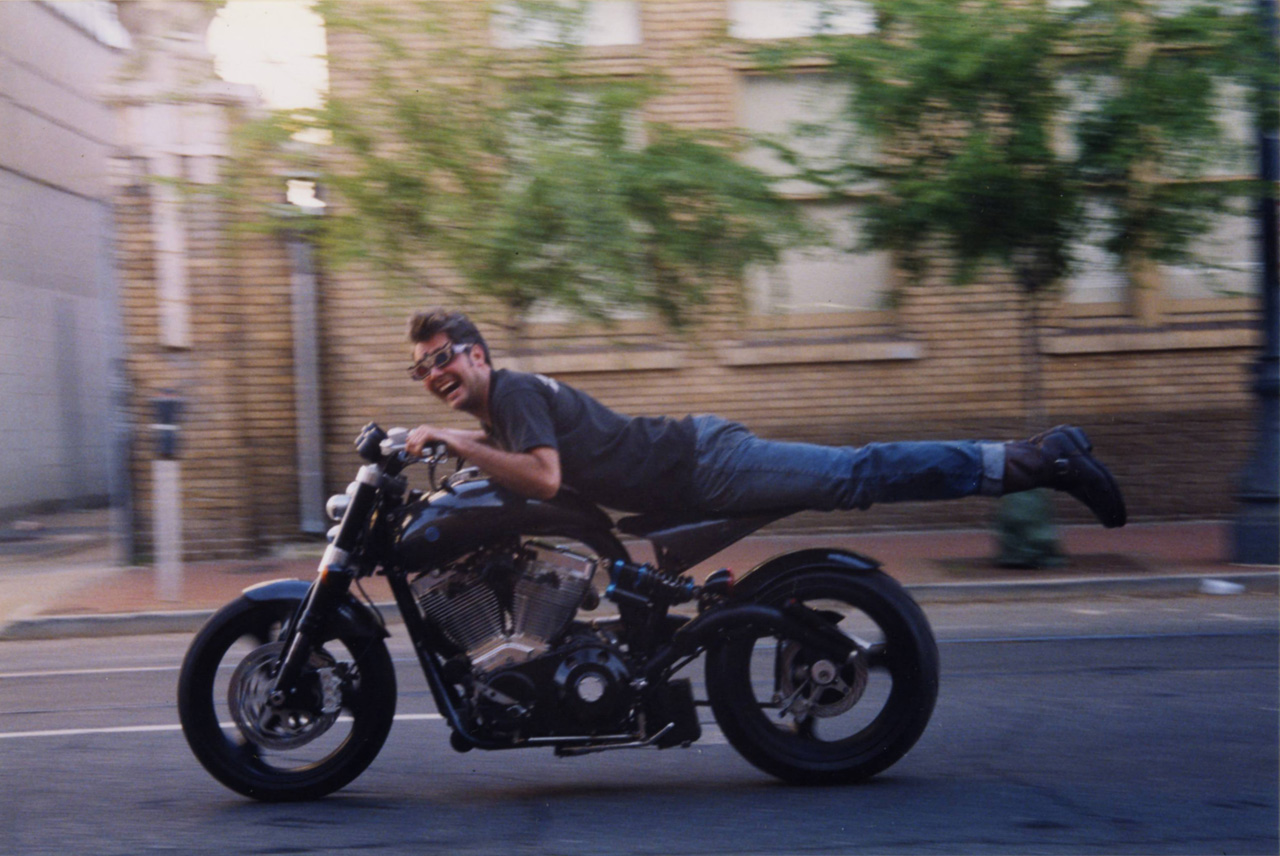

![Woody McNobrake Woody McNobrake]()

This should be an epicenter of Canadian motorcycling. But it isn't. And consequently the Calgary show sucks.

But I digress. My seasonal vitamin-D deficiency is manifesting itself in undue bitterness. You try being a passionate motorcyclist in a land where your riding season is six months long,

on a good year, in a city where you've witnessed snowstorms in the middle of

September.

I was curious to see some of the new offerings, though in general I've found this year to be quite disappointing in terms of new models. Conservatism seems to be rampant outside of a few high-profile aberrations that have (rightfully) grabbed the public's attention. This probably shouldn't come as a surprise – the fact that there are neat machines getting built at all should be the shocker. We are still in the midst of a slump and plummeting oil prices are screwing with the market, despite misplaced optimism that maybe the economy is really picking up (for real this time, honest,

dear God please), and most of the models that are being released now had their design briefs finalized during the depths of the recession.

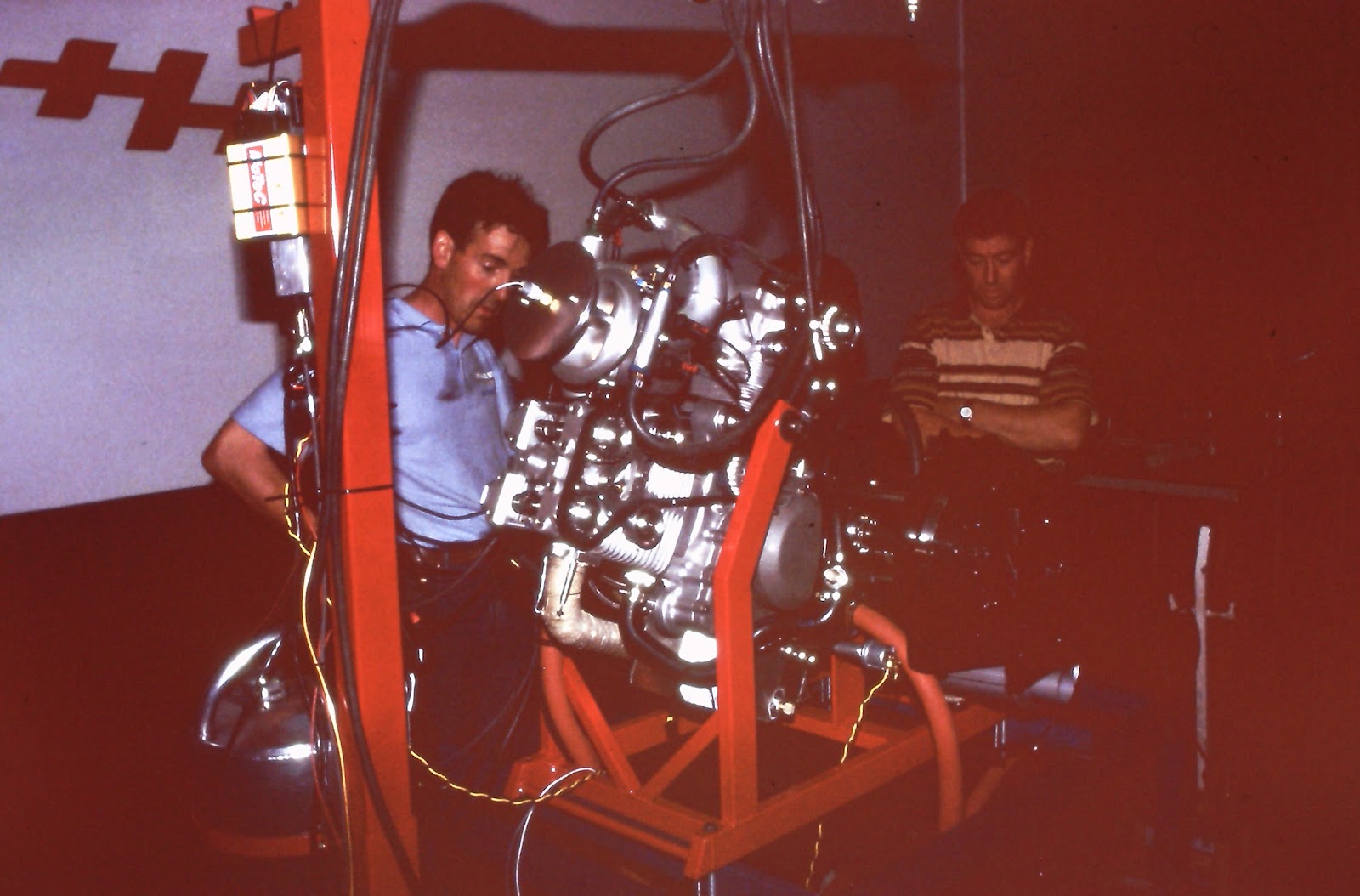

Star of the show was undoubtedly the

Kawasaki H2R. This thing, despite all criticisms, is amazing - the best kind of batshit lunacy you can buy over the counter with a factory warranty. The mere fact that Kawi had the balls to build something so utterly, ridiculously over the top nearly makes up for the atrocious styling and handbag liner seat of the

Z1000. We need more off-the-wall engineering exercises like the H2R to spur on an arms race in what has become a terribly boring industry that has been chasing points in worthless magazine shootouts for far too long. It doesn't matter that the H2R is ugly, exorbitantly expensive (55,000$ here in Canada), not street legal, or that the

H2 street version is detuned and overweight to the point of being eclipsed by the latest batch of superbikes before it even left the factory. Kawasaki engineers have built something impressive, pointless, and excessive, a fantastic display of engineering prowess born from the mere act of leaving the bean counters out of the equation. The finish and quality of the prototype on display was superb and it is clearly ready for mass production.

Three H2Rs have already been sold in Canada, along with a handful of H2s. I wouldn't say it is better than an equivalently priced Bimota, but it's undeniably cool and the fact that the Japanese have built it marks, for me, a return to form. The Japanese are at their best when they are given the freedom to exercise their engineering prowess, not when they are busy chasing Joe Average’s bottom dollar by making budget knockoffs of more interesting machines. The former is what inspires action and pushes the industry forward, the latter is what gives accountants a hardon.

Yamaha brought along a lone

YZF-R1M for the masses to drool over, and truth be told it is quite a nice looking machine. Quality appears to be higher than usual for a production Japanese machine, with glossy carbon-fibre, a brushed alloy fuel tank, sharp TFT dash, and tasty electronically adjustable Ohlins goodies on both ends. If anything the styling is dull, and it looks weird by lacking a "face" due to those minimal lights up front, but the specifications and technology on display more than makes up for it. It's a handsome machine when you see it in person. The only major gripe I can muster is the idiotic projector beams tacked under the nose like an afterthought. The LED running lights set into the nose look cool as balls, but those main beams look like streetfighter cast offs bought from the AutoZone discount bin. On the plus side they are easy to take off for trackdays, which is probably the whole point.

![Yamaha YZF-R1M Yamaha YZF-R1M]()

Whatever the specs, the new R1 will naturally deliver obscene levels of razor-sharp performance... Just like every single other superbike on the market. No matter what the those contrived magazine comparos would lead you to believe, every single one of these machines is ridiculously overpowered and has capabilities so far beyond your conception that calling one better than another and putting together absurd score cards based on press release drivel is some of the most pedantic bullshit you can engage in as a quote-unquote “journalist”. As far as I’m concerned, if you are a mortal human street rider your entire experience aboard one of these time-space disruptors should be reduced to shrieks of euphoric delight punctuated by moments of abject terror, with an overwhelming sense of relief at the end of a not-fatal ride. If you aren't gibbering like an idiot after twisting the throttle to the stop on a clear road, then you are have no soul. Only seasoned racers have any right to comment on the superhuman capabilities of these machines, which is why you should be reading the reviews in

Road Racing World for accurate summaries of what is and is not good on these brutes. Otherwise ignore ALL of it and just buy whatever tickles your prostate and fits your budget.

There was a pleasant surprise found at the Yamaha booth, one that is likely going to get overlooked by everyone drooling over the R1: the

FJ-09. Forget all the pretenses of it being an “adventure tourer” – it's not, and never will be. It's far too light, slim, nimble and handsome to fall into that category, and it comes with 17 inch wheels shod with honest-to-God street tires. Like the

Kawasaki Versys, it's a neat little everyday middleweight that fills the gap left by the wholesale abandonment of the sport touring category. Unlike the Versys, it's good looking, has some really nice quality components, and uses the awesome little 847cc triple pulled straight out of the

FZ-09 but with the shitty fuel injection and garbage suspension sorted out.

If the FJ-09 has any major flaw it is that it is innocuous to the point of being invisible – it turned out that we had two of these sitting in the showroom of the dealer where I work, and I hadn't noticed them for over a month. Oops. I hope that doesn't discourage buyers, because this is a sweet little machine that fills a niche that has long been neglected – a proper lightweight sport tourer with a fun motor and good handing that weighs under 500 lbs and isn't a BMW GS knockoff. It’s also 11 grand (CDN), which is probably the bargain of the year, though they will charge you a fair bit extra if you want the factory hard bags... Not that any company throws in free luggage on anything smaller than a Goldwing. If I was in the market for a touring bike of any description the FJ-09 would be first pick on my list.

Between the R1, the FJ-09, last year's appealing FZ-09, and the class-leading

FZ-07, I think Yamaha is on a roll making good stuff for the common rider.

Continuing with the Japanese contingent: Honda had nothing notable on display. The most interesting thing they brought along was a clean, first generation GL1000, to give you an indication of how boring the lineup was this year. There was the updated

VFR800, which looks more dated than the outgoing Interceptor despite being a fair bit lighter and more modern under the dull exterior. There was the goofy and expensive (12,499$, a mere 100$ less than a 2015 CBR600RR)

NM4 Vultus, which is what happens when a company collectively forgets one their failures (

DN-01) so hard that they repeat it verbatim a few years later.

Then there was the

CBR300 and the latest versions of the 700 twins and… oh God I can't even muster the slightest bit of interest in any of these catastrophically tedious appliances.

Moving on.

Suzuki rounded things out by showing almost nothing new. The

2015 GSXR differs from the 2014 only in paint, they brought back the

DRZ400SM virtually unchanged from when they discontinued it in 2008, along with the

SV650S which is also unchanged - yes, American readers, they still sell the semi-faired SV up here right alongside the overcooked

SFV. The company hasn't been doing so hot lately, what with their automotive arm imploding, so it's probably not a surprise to see they are rehashing the same ol' to save money. They did bring two of the new

GSX-S750 models, which proved to be a handsome little standard and a welcome addition to a category that has been neglected for years in North America. Mercifully they didn't bring the budgie-faced

GSX-S1000F, which has to be the most comically styled motorcycle I've seen since Buell went tits up.

Speaking of Buell,

Erik Buell Racing was notably absent. Despite having Parts Unlimited as their, uh, parts distributor in the United States, there has been no word whatsoever about bringing EBR up into the frigid tundra, which would be presumably done through PU’s poor Northern brother Parts Canada. Motovan, a major rival to Parts Canada up here, acts as the distributor for MV Agusta so it would make sense for Parts Can to get into the game with EBR.

Or maybe it wouldn't. I don't care. I just really want them to be sold up here, and I really genuinely want them to see them succeed.

I've been quite impressed with what Erik Buell has accomplished in the years since Harley-Davidson shuttered his company. I had the opportunity to examine the new

1190RX and

SX in detail while visiting the Barber Vintage Festival this past October, as well as attend a charity dinner that had Erik as the guest of honor. I had the chance to talk to Buell briefly. He is in a great position;

Hero MotoCorp provides the funding and the stability, while his team in Wisconsin provides Hero with R&D. He was quite proud of his team's work for Hero, which has largely been ignored – EBR has built 13 concept vehicles for Hero since their partnership began, all of which have earned Hero quite a bit of acclaim. It might not go over so well in India if word was spread that the high-profile concepts of a local company were designed and built in America, a curious turn of circumstances in a world where Harley-Davidson is quietly putting together bikes in Bawal.

The RX and SX are nice looking motorcycles, and all signs point to them being a hoot to ride. Having had the opportunity to examine them next to the

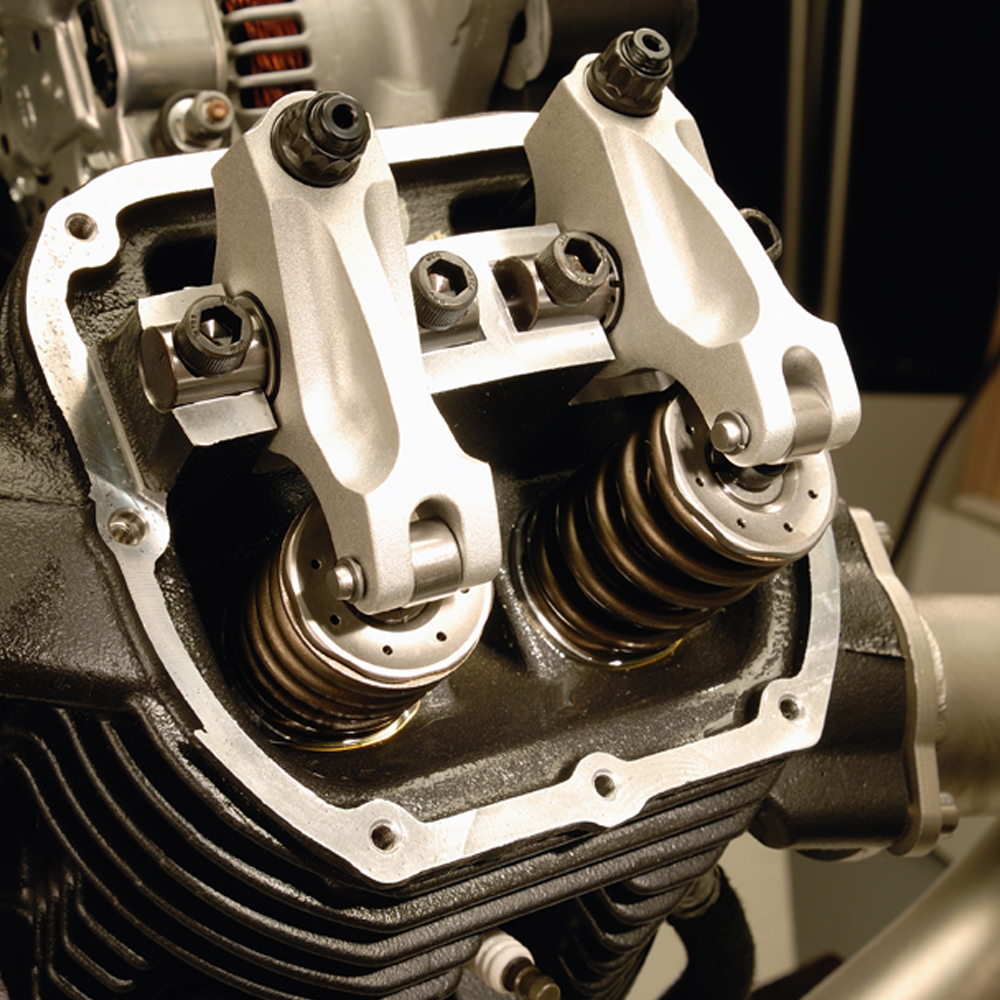

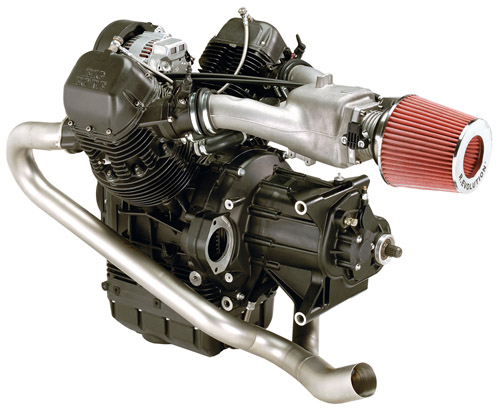

1190RS, I can safely say that they share a lot more in common with that limited-production 46,495$ USD beast than even EBR has let on. The frame, subframe and swingarm are identical, the RX/SX have better looking bodywork, finish quality is equal (and quite good for a small startup), and power is up substantially while still meeting all the requisite emission and noise regulations. The only place the RX/SX lag the RS is in suspension components and their lack of carbon-fibre bodywork, which is acceptable considering they retail for less than half the price. Buell's trademark weirdness is still present with their fuel in frame chassis and perimeter brake, but aside from that the new frame and engine share nothing in common with the swansong

1125R– Harley still owns the rights to the Buell name and the 1125, so EBR set about reverse engineering the 1125 and making it better in every respect without infringing on HD's patents. The 1190 engine is made in-house by EBR and was heavily revised by their engineers compared to the Rotax-made 1125. The 1190 represents similar ideas to the 1125 but with different execution. I thought the 1125 was an awesome machine (marred only by some of the most godawful fuel injection subjected upon the buying public), so the thought of a highly polished successor with 40 more horsepower and far better styling is truly tantalizing to me. I want one, and I sincerely hope EBR does well, and is given a fair shake by our ever-skeptical market. They just need to get their act together and find a Canadian distributor.

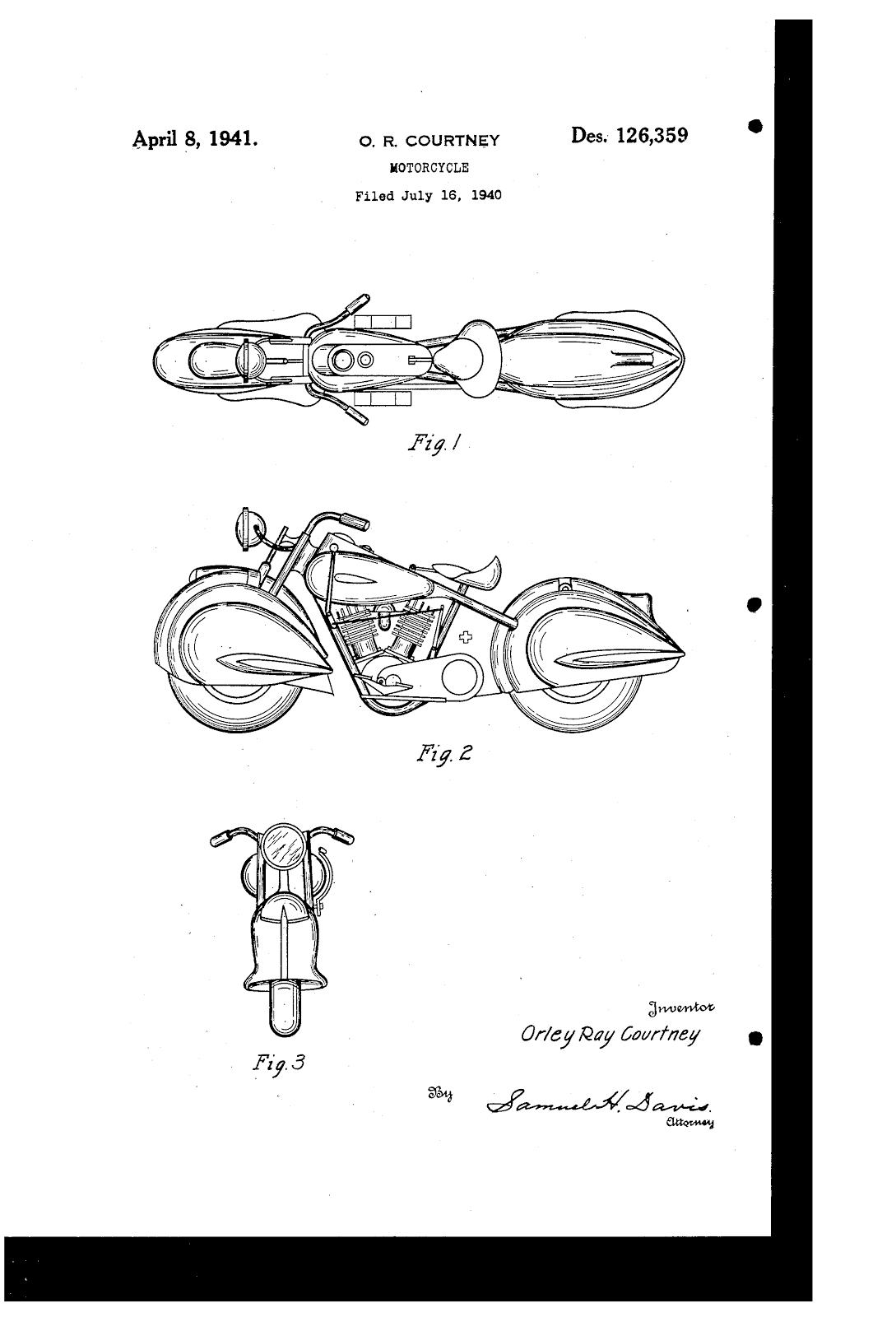

Harley-Davidson was present, and laughably out of touch as would be expected. While the execrable "

Urban. Authentic. Soul."

Street 500/750s took centre stage alongside a couple of luridly awful custom jobs based upon them, two – count em'–

TWOLivewire prototypes were relegated to a remote corner of the show. They were setup in what looked more like a stand for a local bike club than a cost-no-object display of the forward-thinking engineering prowess of America’s motorcycle kingpin. They proved to be an interesting distraction and the only electric machines present aside from some Oset kiddie trials bikes.

![Harley-Davidson Livewire Harley-Davidson Livewire]() |

| I apologize for not getting any decent shots of the Livewire. It was due to the huge crowd that was milling around the booth. The same could not be said about the Hipsterbait 500/750 display. Are you taking notes, Harley? |

I poked through a tablet setup in the booth with a digital contest entry form… To win a Street model, and sign up for updates on the Street series. Sigh. They could not have missed the mark more if they tried, but this wasn't a surprise. Despite a throng of curious onlookers crowding the Livewire display, where they were letting people run up the bike on a set of rollers to get a feel for how the electric motor behaved, Harley is horny to push to their entry-level Street onto young, beginning riders who they are desperate to lure into their fold. The terrible custom jobs on display at centre stage were clearly aimed at budding chop and hack artists (and appeared to be put together by them as well).

A chipper 20-something salesperson misinterpreted my gaze of pained disgust as a sign of interest and tried to corner me to tell me all about this cool new Street model and how these custom bikes were built by… Before he shut up and moved on to other targets when he realized I didn't remotely give a shit. The demographics are getting older and Harley is looking to seduce the youth with what looks like their budget interpretation of a Honda Shadow... Built in India (sorry, “

Assembled in Kansas”) with component quality that would cost a Honda employee their head.

![Harley-Davidson's Marketing Strategy Harley-Davidson's Marketing Strategy]() |

| Harley-Davidson's marketing strategy. |

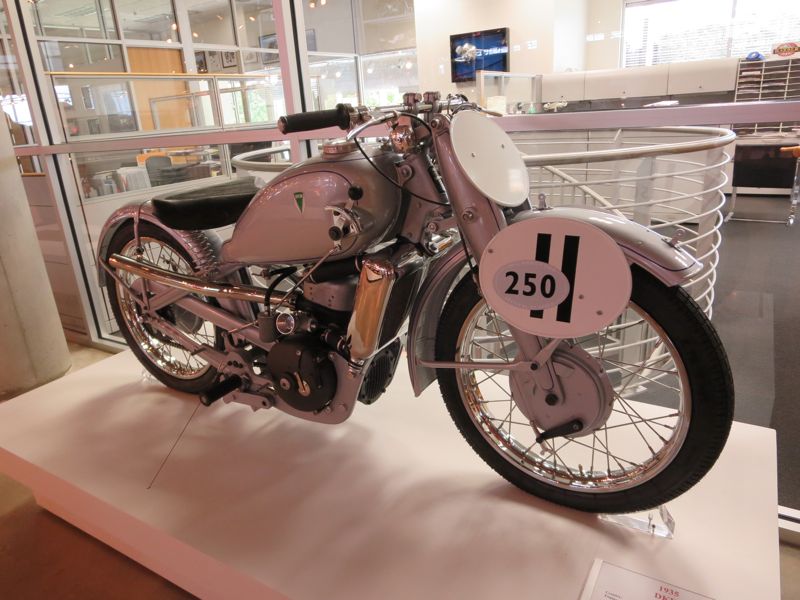

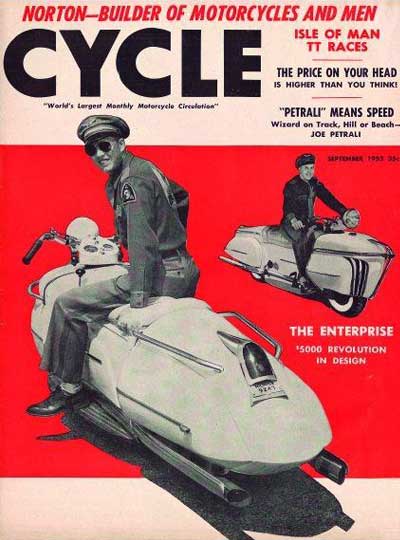

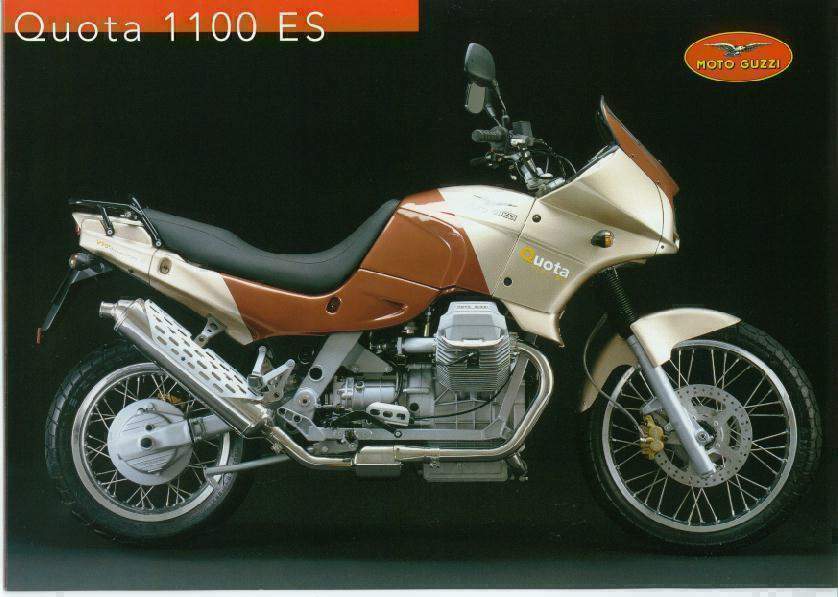

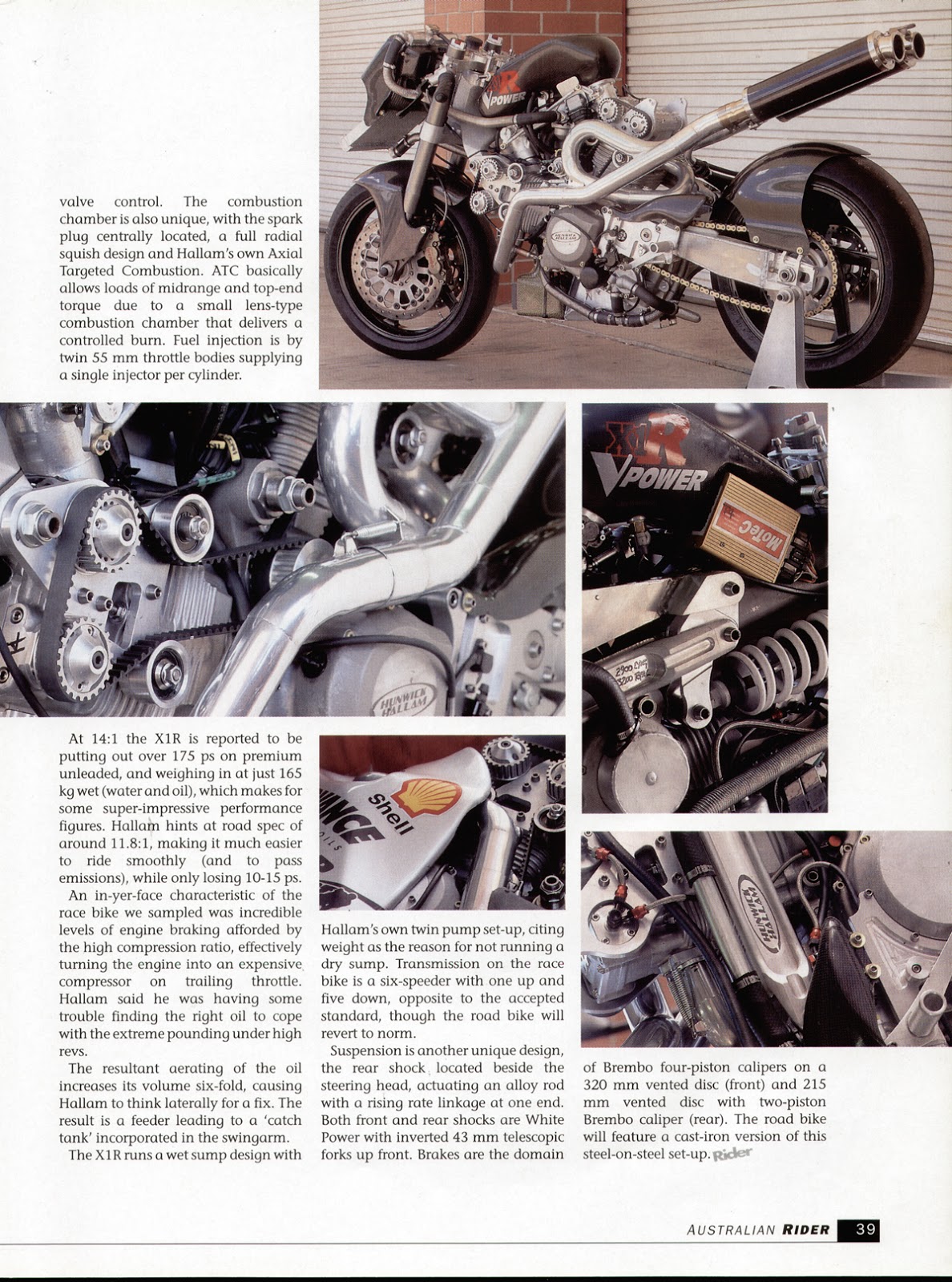

Meanwhile, the Europeans are busy doing their own thing. Ducati brought along several

Scrambler models and a stage dedicated to them alone, replete with faux-woodsy motif and astroturf to complete the illusion of rugged individualism for the flannel-and-beard set. A single

1299 Panigale S (identical to the 1199 outside of the motor and some subtle chassis tweaks) was shunted into the opposite corner; long gone are the days when Ducati used their magnificent sportbikes as flagship models, apparently. There were more

Diavels present than anything else, a sure sign of the apocalypse if you are a die-hard Ducatisti. I walked away from the stand with zero desire to own another Duc, a sentiment I've felt for a few years now – the

1098R or

1198SP would be the latest Ducs I'd consider owning, everything that has followed those brutes has left me cold. That's why when it came to adding another bike to my stable, I bought a used Aprilia Tuono to supplement my 916.

![Ducati Scrambler Ducati Scrambler]()

The Scrambler is clearly Ducati's new golden boy, and at a glance you'd be forgiven for thinking they've thrown all their eggs into that particular basket. The hype and marketing has been ridiculous, in scope and in content. In terms of the bike, it is clearly a tarted-up replacement for the discontinued Monster 696/796, a fact that most reviewers appear to have overlooked – it is thus the last Ducati to use the evergreen air-cooled 2-valve Pantah engine, which has been steadily phased out of the company's lineup due to increasingly tight emissions regulations. The fact the Scrambler uses the 2V engine came as a bit of a shock to us pundits who been anticipating this model for several years – we expected them to dump the Pantah architecture after the Monster series took on the liquid-cooled Testastrettas across the board. Whatever the grim realities of emissions laws, it serves for a cheap platform to slot into a new model, and it suits the target market – the 803cc is a good “little” motor and has a nice friendly powerband, and is stone-axe reliable and well developed as far as Ducati engines go. Also, the tooling was paid off sometime 30 years ago so Ducati should make a tidy profit on the Scrambler despite it being a brand new entry-level model.

![Ducati Scrambler Ducati Scrambler]()

The Scramblers are cheap, and they will sell a ton of them. They have them aimed squarely at the

Triumph Bonneville/Scrambler/Thruxton,

Hipsterbait Street, and

Moto Guzzi V7 in terms of price and image – and in this crowd they likely won’t have much trouble kicking ass. The initial reviews have been incredibly vague, apparently pawned off onto the newbie journalists (because it's an entry level bike?) who have been so wishy-washy in their impressions they might as well be reviewing a Toyota Camry from the backseat. That being said they appear well put together and are more than likely fun to ride - they won't have much trouble burying their asthmatic competitors. Styling wise I’d call them a miss, though plenty of people seem to like them. To me they look like cartoony, toy-like facsimiles of the original bevel-head Scramblers.

I had the opportunity to sit down with Pierre Terblanche while visiting the

Confederate factory last year and spent a while talking bikes, in particular about his work on the SportClassics and the design of the new Scrambler. He dug around on his computer and pulled up a photograph of a studio mockup he had made around the mid-2000s. It was clearly a “Scrambler”, but one that was far more handsome and mature than the Fisher-Price caricature that Ducati has seen fit to release. To get an idea of what he showed me, picture a Sport 1000 with taller suspension, high bars, repro Scrambler tank, and knobby tires. It was a relatively simple series of changes that would have been easy to put into production, and it looked good. It would have fit right into the whole street scrambler fad... And he had it ready to go 10 years ago. But of course at the time the SportClassics were completely under-appreciated and came out too far ahead of the explosion of the neoclassical retro motorcycle craze; with sales of the SC in the toilet Ducati took the short-sighted path and made the knee-jerk reaction of choosing to abandon the lineup instead of developing it and amortizing the costs to remain competitive. Terblanche wouldn't say “I told you so”, so I’ll say it for him: I’ll bet the management at Ducati was mighty embarrassed when they realized what they had fucked up after they unceremoniously dumped the whole SportClassic line.

![Fisher-Price Scrambler Fisher-Price Scrambler]()

I'll also say that I was once a Terblanche-hater, but time has proven him to have remarkable foresight and his designs look better today than they ever did when they were current – nevermind that he had several popular designs under his belt that his critics are frighteningly quick to forget about, including the 888, the Supermono and the Hypermotard. After having had the chance to hang out with him and talk shop and design, I’m happy to admit I was wrong and I have earned a new found appreciation for his work. How he will fare now that he is moving to

Royal Enfield remains a mystery to me; there are only so many ways you can restyle a

Bullet, so I hope for Pierre’s sake they are working on something new and modern upon which he can really flex his abilities.

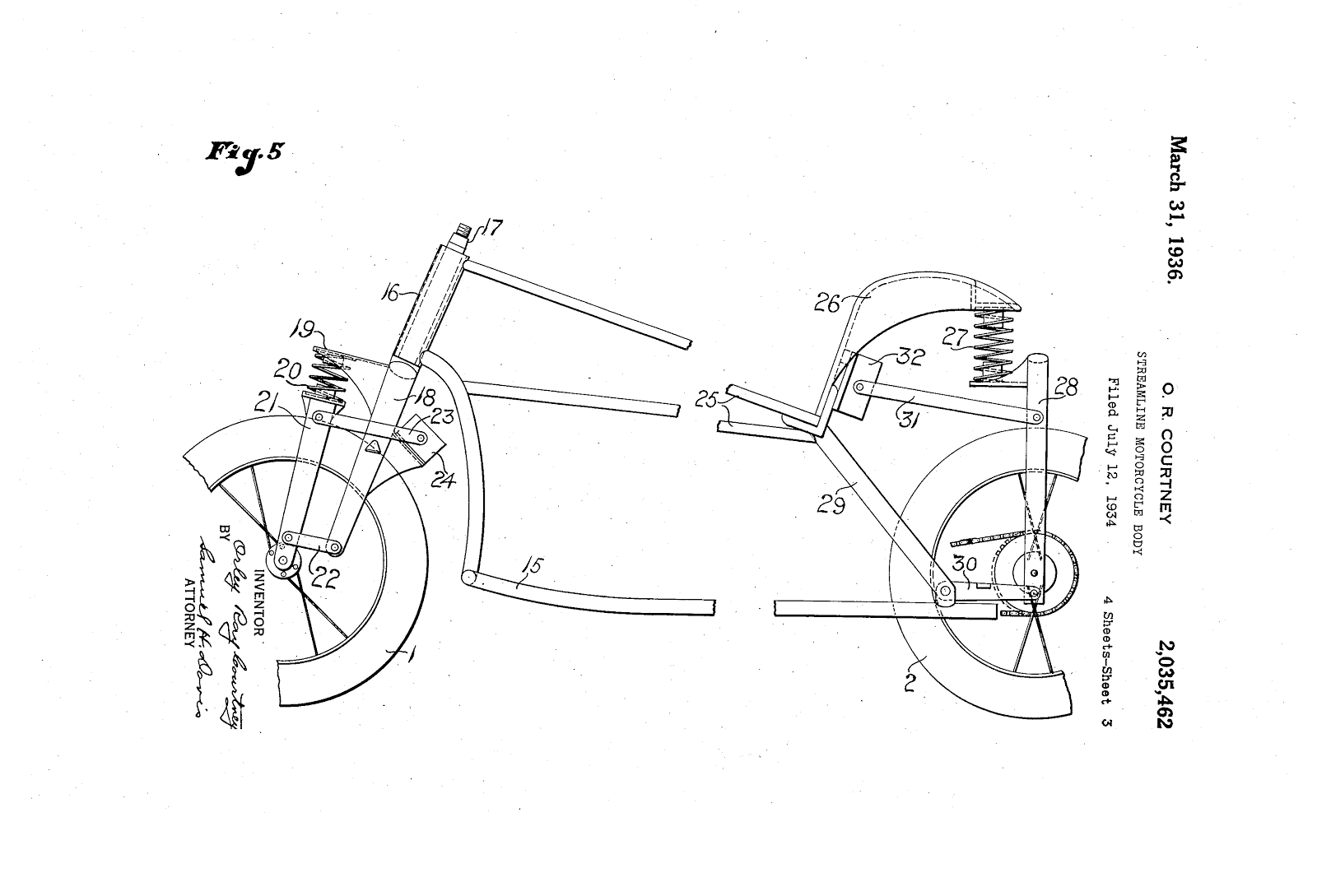

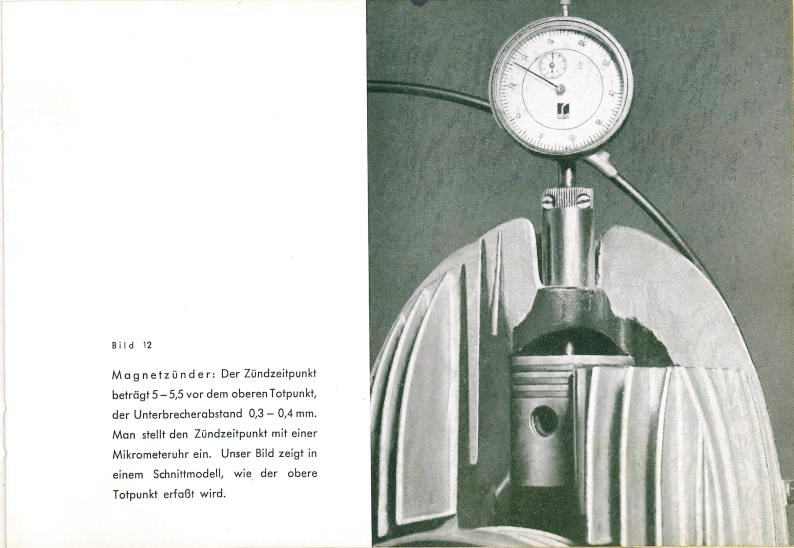

Over at MV Agusta the latest models were present, though the long-announced (but not terribly anticipated)

Turismo Veloce was AWOL. Continuing their milking of the tre-pistone architecture appeared to be the order of the day. The

Brutale and

Dragster RR were hogging the limelight, with flashy paint and impressive tubeless spoke rims on the Dragster - which look far better in red/black than the red/white/black. The white rimmed machine looks like the motorcycle equivalent of a pair of white Nike pumps and a sideways baseball cap. The

Stradale was also on display, which has got to be one of the least anticipated successes of the past year. Somehow taking the

Rivale, which was noted to be the least suitable MV for riding further than the nearest Starbucks, and slapping on some tiny bags, an ugly windshield, and a bigger fuel tank transformed it into the most streetable MV in the lineup. It's a sport tourer that should not work, but somehow does and it has been defying all expectations. It also looks like a mess, like someone vomited the contents of the Vespa accessory catalogue onto a Rivale.

The unfortunate side of this multiplication of the lineup (in the three-cylinder line alone there are six distinct models) are some signs of cost-cutting, stuff that has traditionally been beneath MV who have always been notable for their superb build quality. The triples are inexpensive as far as MVs go and they have begun to suffer when compared to the

F4, which was always a benchmark in terms of component quality and tidy finishing. Cheap castings, exposed wiring and connectors, and bits made of zinc-plated pot metal are starting to pop up on the newest bikes. Not a good sign, but one that is unfortunately understandable considering they are slapping these out for thousands less and in far greater quantities than anything in the F4/

Brutale 4 lines.

On the plus side, word on the street is that MV’s fuel mapping and electronics packages have been refined a lot since their introduction - meaningful progress, because according to some reliable sources they were virtually unrideable in their initial setups. Not that that is unique to MV in our ride-by-wire age – the first maps on the FZ-09 had awful throttle response, though most reviewers were happy to downplay the problem in favour of parroting the launch hype. Take note of how many reviews of the FJ-09 mention how improved the fueling is compared to the FZ.

![MV Agusta Dragster RR MV Agusta Dragster RR]() |

| Note the cheap zinc-plated pieces bolted on the centre of the bar clamp. |

Quality gripes aside, these MVs are still exceptionally pretty motorcycles (except for the Stradale) and I still want one (but not a Stradale), all flaws be goddamned. The

F3 and

F4 remain benchmarks of how a sportbike should look, and will endure for a long time as mouth-watering examples of why Massimo Tamburini was one of the finest motorcycle designers of our generation.

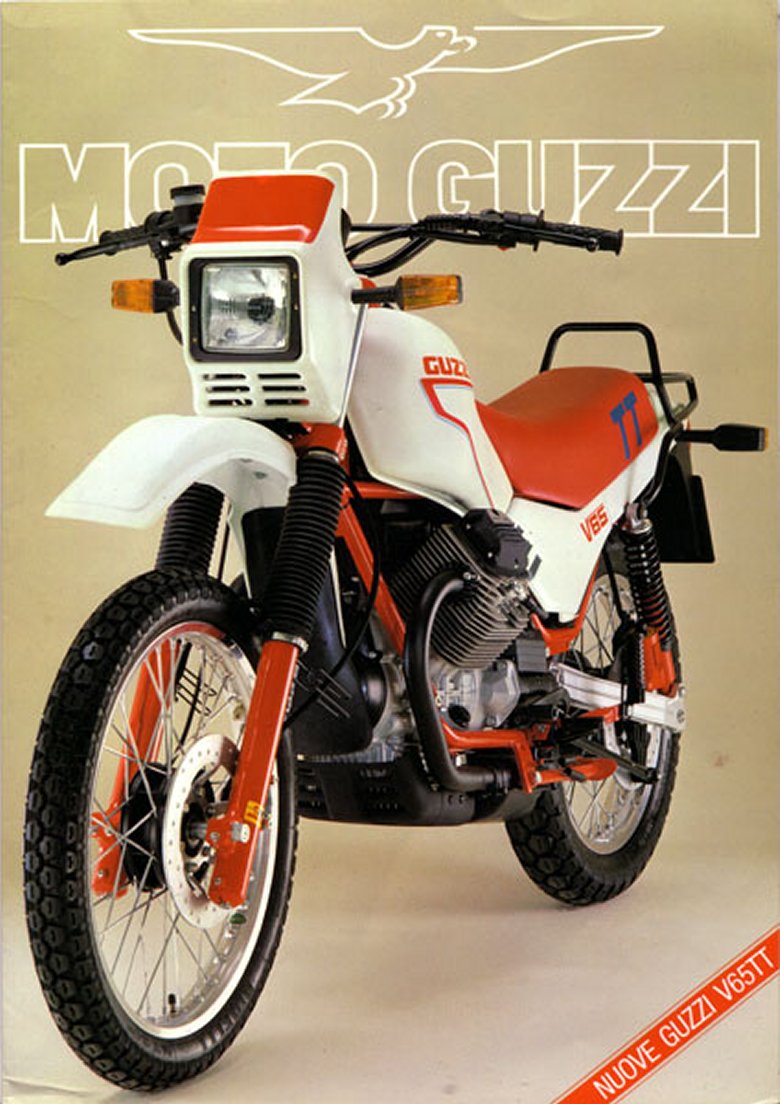

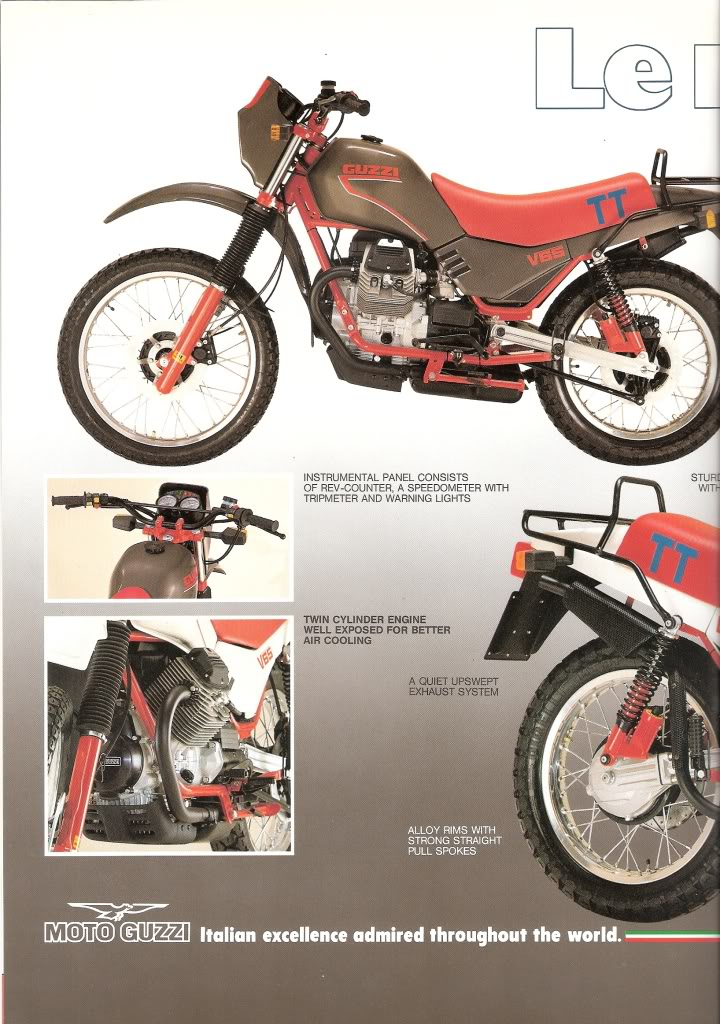

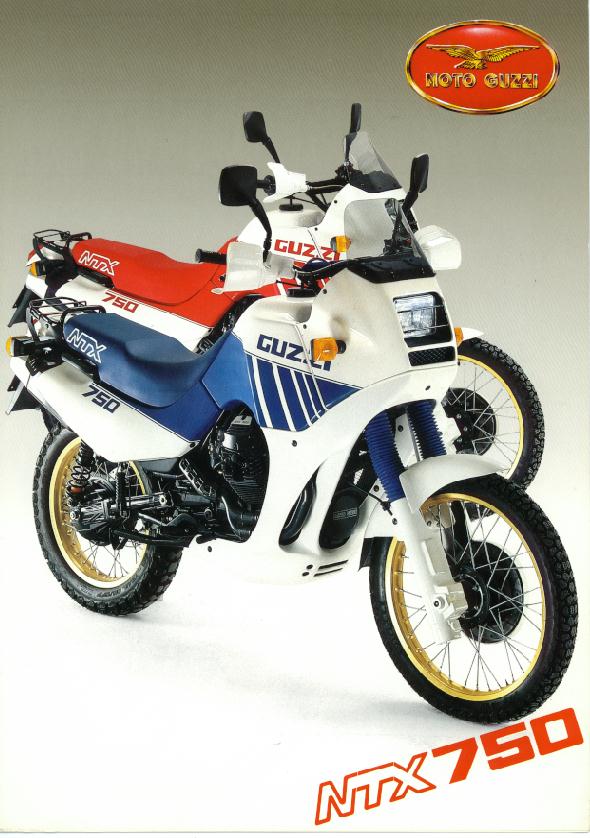

Nothing notable was new from

Moto Guzzi aside from some new colour schemes, as you'd expect from Piaggio's

perennially neglected brand. At the other end of the spectrum the new

Aprilia RSV4 and Tuono 1100 were absent. The only bikes on display were 2014 models from dealer stock. The Piaggio group always has a magical way of making great motorcycles look exceptionally dull and under appreciated by way of their special blend of neglect and a complete lack of effective marketing... Especially here in Canada, where Aprilias and Guzzis seem to be slightly less common than Vincents.

Over at BMW, the boys from Bavaria were showcasing their newly revamped boxer line which included the new

R1200R and

R1200RS. These, in my mind, represent a move in the wrong direction for one reason alone: they dump the Telelever front suspension in favour of cheap, non-adjustable telescopic forks. I don’t care if they are excellent bikes, and have superb handling in spite of this; I don’t even care if the upside down forks they share with the

R Nine T perform better than the outgoing Telelever setup. I’m sure they are great bikes and will work perfectly well. However, to me, a deranged blogger who values oddities and unique features in a sea of conservative design, BMW’s move away from their signature funny front ends represents an abandonment of the admirable cost-no-object risk taking they exhibited when they adopted those weird-ass suspensions in the first place. It is also, in my mind, a clear case of tightwad cost cutting.

The new

S1000RR was nice but not particularly noteworthy outside of the usual class-chasing tweaks to put them back at the top of the spec sheet wars. The only comment I can really muster is it looks slightly less ugly with its softened face, which has abandoned its Cubist interpretation of a headlight. The updates will surely please the chicken-strip and carbon-fibre set who seem to gravitate towards them.

A pleasant surprise at the KTM booth was the inclusion of the

Duke 390 and

RC390. They represent a smart move towards genuinely good entry level machines that will appeal to new riders without the stigma surrounding the shitty entry-level crap that has been pawned off on North American riders for years. Sure, we haven't appreciated anything under 600ccs and our open licensing system has kept sales of sensible machines in the low-to-nonexistent range, but continuing to offer nothing better than unsexy antiquated crap like the Ninja 250-300-400 hasn't helped matters. One of my first bikes was a Japanese import Honda

NC24 VFR400R, which proved to be about the most fun you could have with less than 100 hp and a fantastic introduction to sport riding with something that was cool, desirable, and not dumbed down in any way. I was totally sold on the value of high-quality small sportbikes and I've since been disappointed by how this category has been completely ignored outside of the Japanese home market.

That being said I'm not delusional - those JDM 400s and 250s would ever achieve any success beyond a cult following here because they are too small, too expensive, and will never appeal to the bigger-is-better and fastest-is-best crowd.

The 390s represent something quite special, a tentative first step towards bringing that kind of small-bore fun to the Americas – and unlike the JDM imports, they have an extremely accessible price tag while still looking like proper machines. However, the efforts to get the price down are clear at a glance – quality appears to be middling. They still look better than anything in the category right now; the Yamaha R3 was also present and looked half-decent with perhaps slightly better build quality (reviews are still pending), but they didn't exude quite the same cool factor as the 390s. And that's where KTM has a potential winner on their hands: the 390s are cool and people want them.

KTM has been on a roll lately, and had their latest

1190 and

1290 Adventures on hand (but not the Euro Regulation Special 1050). The

1290R Superduke was also present, and has been making everyone go weak-knee'd for several months. We've had a few pass through the shop already and they are truly an exceptional machine - one of the finest, maddest streetfighters of all time and a fantastic throwdown that KTM's competition had better heed. It looks amazing and the motor is apparently one of the greatest motorcycle engines of all time: owners report that it if treated gently it is docile and smooth, and easy to ride in traffic, but one stiff twist of the wrist and it will rip your goddamned face off and make you thankful for the comprehensive traction control package. 100 mph power wheelies are available. This thing is ridiculous in the best possible way. It also

sounds apocalyptic with a decent pipe - the hot ticket is an

Austin Racing slip-on (be sure ride it at least once without the baffle).

![KTM RC390 KTM RC390]() |

| You've already seen plenty of pictures of the 1290R. I also may have forgotten to snap any shots of it. So here's more of the 390s! |

The

original Aprilia Tuono showed the way to achieve motorcycling nirvana – take a sportbike, remove the fairings, put high bars, then leave the rest the hell alone. No detuning, no dumbing down, no diluting the experience. The Superduke takes this to the next level by building a vicious naked sportbike from the ground up – it isn't based on anything pre-existing and it sure as hell hasn't been softened up because it lacks clip-ons and a fairing. It’s everything we lunatic sport riders have ever wanted, while still being entirely usable every day, and I sincerely hope it inspires other brands to follow suit. The current competition got caught with their pants down, and now they are going to have to work hard to reach the new high water mark. Yes, the retail price is high (18,999$ up here), but damned if it isn't worth it in this case.

It’s funny that the Superduke has gotten so much good press and rabid attention, because Ducati had the same kind of machine in showrooms not that long ago – the

Streetfighter 1098 was a ridiculously fast, vicious, no-compromise naked sport bike that everyone claimed they wanted but nobody actually bought once they released it (see also: SportClassic). Unlike the KTM it lacked civility in daily use, which ended up being the major gripe against it, along with a high price tag. Despite giving the people what they wanted, reviews were whiny and gave the SF1098 middling marks, often making the unfair

comparison between the SF and the full-fat 1198 and then concluding that the 1198 was a better sportbike (...duh?). Sales suffered for a while before Ducati finally gave up, dropping the SF1098 while leaving the far duller SF848 in production. Then, shortly after it was axed, the SF1098 earned a dedicated cult following and secondary market pricing has remained very high (see also: SportClassic).

Somehow the equally (perhaps more) nuts Aprilia Tuono V4 ended up becoming a darling of reviewers despite being worse as a daily rider than the Streetfighter - the thousands-less price tag probably contributed to it becoming the poster boy for the category while the Duc got damned with faint praise. Ducati gave up and went on to build the fat and fluffy Monster 821/1200. Rumours are circulating that they might, maybe,

should build a naked Panigale, but given how they got burned on the Streetfighter I'd currently give those rumours as much credence as the imminent return of the Supermono... Unless they take a look at the Superduke and decide they want a piece of that sexy, sexy pie rather than shitting out another Diavel variant.

So long as the Superduke avoids the fate of the Streetfighter, it might be just what we need to wake up the naked sportbike market and inspire a new generation of bonkers, undiluted streetfighters. I for one welcome our new brutal overlords.

Of course you already knew that, because the Superduke has been getting praised and hyped ad-nauseum via every possible venue. I hate to propagate the myth, but damned if I don't want to get a ride on one. It won't happen though, because up here the 1290R is being treated like an exotic, unobtainable superstar. Nobody is getting seat time unless they have cash in hand or are a quote-unquote “real” journalist.

So, overall impressions for this year are that most companies appear to be erring on the cautious side. Outside of a few exceptional diversions most everything is terribly boring and barely noteworthy, much every year since the economy took a dump in 2008. We are barely out of the depths of the recession and it has really taken its toll on the market - when companies like Ducati and Harley are pushing their budget, entry-level models to the point of overshadowing their flagships, you know priorities are getting skewed in the wrong direction. Blindly chasing the consumer’s bottom dollar is never a good sign, particularly if you desperately want to see some innovation. There are, however, a few bright points - Yamaha is making good, appealing, accessible stuff, Kawasaki is making the bonkers H2 series, KTM is kicking ass and taking names at the top while also bringing in some sexy entry level machinery at the bottom, while south of the border EBR is showing that the folks in Wisconsin can build some world class sportbikes. Let's hope these stellar examples inspire some more innovation and competition: the rest of the industry should be taking note of what KTM, EBR, Yamaha, and Kawasaki are doing and ignoring the bullshit from everyone else.

Complete Picasa photo album